Why Development *Is* About Security, Stability, and Growth

/By Carol Marie Tuite

This is our new First Mondays: Policy Perspectives monthly newsletter that brings the cross-cutting topics, connective readings, and diverse viewpoints that we cultivated in our monthly policy salons to the entire Franklin Street network — no matter where in the world you spend your Monday nights. (And if you’re in NYC on July 18th, join us for our Oops! Romney Was Right happy hour.

Policy Perspectives is a packed with links (some fun, some “nutritious”) for you to take a deeper dive on the concepts and points raised. Fired up after reading and want to share your thoughts? Post your rebuttals and responses in comments. Look for Policy Perspectives every first Monday of the month.

In keeping with our framework of quarterly themes at the intersection of global business, development, and security, the next three issues will take a 360-approach to The Business of Development.

Bottom Line Up Front

Markets and businesses like stable environments with reliable recourse and enforcement if their products or services are stolen, copied, slandered, or undercut.

Development assistance is supposed to create stable environments for healthy economies to grow and function smoothly. It is the unsexy, un-viral, technical, plodding, essential, life-changing, game-tweaking-not-game-changing work of building healthy communities.

Healthy communities are built and sustained by healthy people and healthy systems — high-quality, functioning, and integrated education, healthcare, infrastructure, governance (i.e., regulatory agencies, judicial systems, legislative bodies, and law enforcement), revenue (i.e., customs, tax collection), and security processes.

Healthy systems run on cold, hard cash. Good will and a prayer won’t pay for logistics, procurement, operations, production, quality assurance, market research, distribution, business development, and the advanced technology of… well, anything.

Development as an industry is pivoting — in the way a behemoth cruise ship pivots. It needs to pick up the pace to match the speed of modern, tech-enabled human society, to leverage the opportunities of a lately more engaged private sector, and to onboard a world of populist governments who are persuaded more readily by a security argument than an economic one.

The fight in Congress, the media, and the development sector over funding is one that has never been settled calmly in agreement. However, the relationship of global and national security to healthy and dynamic economic markets has brought a renewed focus and nuanced take on development, particularly in fragile areas. The private sector now takes a keen interest in what development means as their supply chains, distribution networks, and search for untapped markets are more transparent — and scrutinized — than ever. All the while, development organizations covet the resources, distribution networks, innovation, and influence on governments that the private sector brings to bear.

The Whats and Whys of Development Aid

Aid matters like the paved road you drive to work on; the fully powered school your kid builds her future in; and the staffed hospital your mother had her heart surgery in matters. These are mundane things from everyday life that are only possible when we live in an economically dynamic and stable system. Development is not supposed to be a bottomless black hole of charity; it’s what every one of today's “first world” countries has been practicing more or less since the Industrial Revolution. The aid relationship between developed and developing countries grew, in many ways, from the complicated ties established during colonial rule and during the post-World War II economic expansion when a decimated global marketplace experienced rapid growth.

So What ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ ?

Recently, the administration announced plans to slash U.S. foreign aid budget by over one-third, renewing the debate about the effectiveness of aid and its impact as NGOs and governments plan for the impending shortfall. Entrepreneurial and conventional corporations alike may take notice as these cuts will affect the workforce, skills, and technical development of their labor and consumer markets overseas. And, a few weeks ago, U.S. Adm. Mike Mullen and Gen. Jim Jones sounded the alarm about why these cuts are detrimental to national security, which “is advanced by the development of stable nations that are making progress on social development, economic growth and good governance; by countries that enforce the rule of law and invest in the health and education of their own people.”

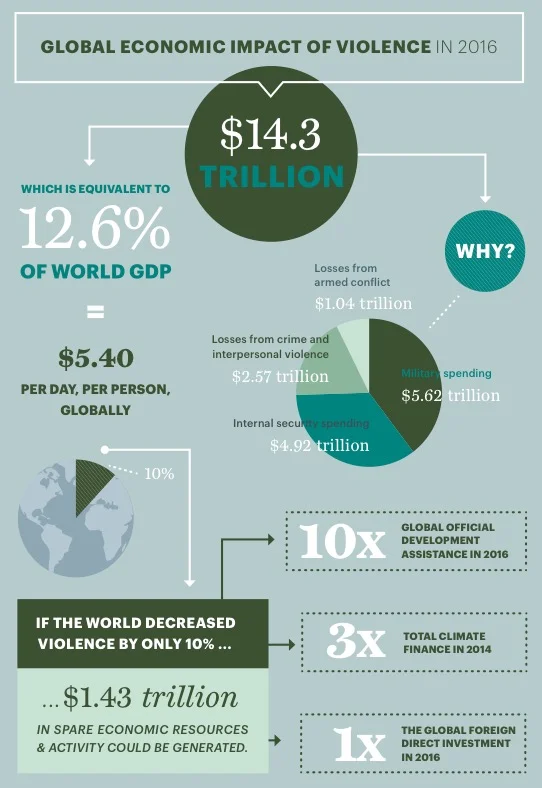

Creating a peaceful environment for healthy human and economic activity ain’t cheap, but its returns are extraordinary. The 2017 Global Peace Index estimates a 1:16 return on investment in global GDP gains captured — 12.6% of global GDP is sacrificed to spending on conflict and security. If the world decreased violence by only 10%, an additional $1.43 trillion of economic activity would be generated by the increased productivity of people currently living without access to quality education, healthcare, and employment opportunities.

What the Skeptics Say (Spoiler: They’re Wrong… But Also a Little Right)

Skeptics argue that indefinite infusions of cash and resources are not sustainable — and may even be detrimental because aid leads to dependency and government corruption. Despite proof of recent successful programs like the Bush administration’s program to reduce malaria, many are on the chopping block, with potentially devastating ripple effects far beyond defunding global health clinics, reading programs, and farmer trainings on soil health (that’s a thing).

Others call for an overhaul on how aid is deployed. Last month, a former UNHCR senior official argued that the aid system was “not designed” to address today’s systemic challenges, with large numbers of refugees displaced for long periods of time by persistent conflict, such as the war in Syria. At present, 20 million people are at risk of starvation in Yemen and Africa due primarily to conflict. Taking on these challenges with any hope of success requires highly coordinated engagement from both obvious and newcomer players at the table: national governments, international relief organizations, local-level service providers, community stakeholders, and private sector actors to do the on-the-ground grunt work of rebuilding entire communities, economies, and the unsexy, essential infrastructure and bureaucracies that support them.

Getting Aid Fit For Life

Transitioning short-term humanitarian aid (think triage in the emergency room) into long-term development (like preventive health checks, a fiber-and-veg-laden diet, and your “daily” exercise routine) has been a challenge for decades. As development organizations grapple with the confluence of global trends that affect their work, their core mission remains to improve lives by building resilient communities through education, healthcare, and economic opportunity. The challenge, unfortunately, also remains that sometimes “big ideas” with big funding from big organizations can start off with a well publicized bang, shoot out of the gate at a slightly awkward gallop, tick along at a directionally challenged wander, and ultimately fail to translate into transformative, sustainable outcomes for healthy systems (see: your last New Year’s resolution to “get fit”).

Instead, programs that are un-sexily technical and incremental — they’re not going to “get shared on UpWorthy or make you reach into your pocket for your PayPal password or whatever” — and implemented on long time lines are the future of development. The addition of innovations from the private sector — like high-precision data collection and analysis tools — help to measure and direct what a development program is supposed to do versus what it actually manages to achieve. Working on patient timelines that are realistic about human behavior and environmental adaptations is also necessary to reverse the effects climate change on drought, landscape devastation brought on by war, and to provide opportunities for young, educated, and underemployed people around the world, especially in post-conflict areas.

How quickly and how well communities develop and grow is not straightforward. Success is constructed carefully, piece by piece — some move easily, others need more coaxing or for other pieces to move first — and the removal of the wrong damn block can lead to all or part of the effort crumbling. Cross-sector investment in the complex, interlinked, poverty-reducing systems of education, healthcare, infrastructure, energy, governance, security, and markets are critical to ensure human, economic, political, and social development and security in an increasingly networked world.

Next month: Cash is King and Paves More Than Roads. How the private sector gets involved.